Note: This piece was written by Rhonda Glenn and originally ran on usga.org on October 28, 2012. Brown died on May 1, 2015, at the age of 80.

Unless you’re Pete Brown, it’s only a few hundred miles from Jackson, Miss., to Augusta, Ga. Brown, however, traveled a hard road, one that wound through Southern California and Ohio, a road littered with hazards and triumph, bad memories and good friends, until finally, he is back in his beloved South.

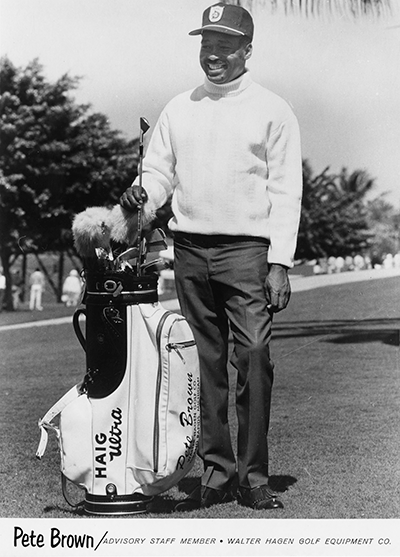

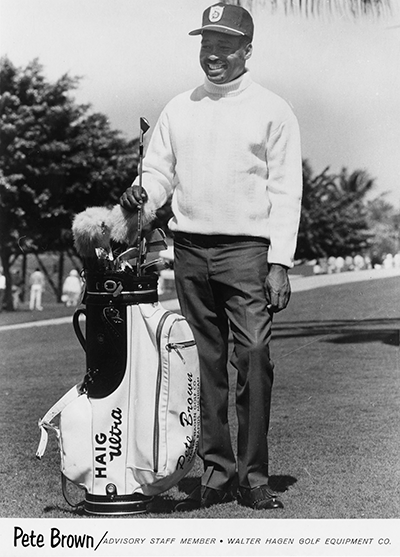

Pete Brown, 77, holds a unique place in golf history – one that only he has filled yet one commensurate with the accomplishments of the more famous Charlie Sifford and Lee Elder. A full generation ago, Pete Brown was the first black player to win on the PGA Tour.

Among black golfers, poverty and post-segregation slights are familiar stories. Brown, like others, overcame them. It was polio, the crippling scourge that plagued so many so long ago, that most threatened Brown’s future and his life.

Like Sifford, Jim Dent and other male golfers of color, Brown came out of the caddie ranks with a self-taught golf swing. At 11, he saw that caddieing offered a bigger payday. He made $6 a day for 36 holes at a public course. Like a lot of black children, the caddies used discarded clubs to hit balls on vacant farmland. In Mississippi, Brown was the best of the lot. By the age of 17, whenever he played a full-length course he broke 70.

That’s when a light went on. Maybe he could make a living playing golf.

He worked on his game, made a few friends, and traveled to tournaments. In Houston, he finished second to Bill Spiller in the Lone Star Open, a tournament for black players. Sifford urged him to stay amateur. “He said I needed experience, but I had to win a little money so I could keep trying to play,” Brown said. “That’s the only reason I turned pro.”

Brown went to Detroit to get in on the betting action. Randolph Wallace, a wealthy black businessman, offered to send him to college. It was 1956 when he suffered a tragic setback. Polio struck Pete Brown and he would spend more than a year in a hospital bed.

“You’d better find another sport,” Brown’s doctor told him. “I don’t think you’ll be able to walk again.”

Mostly ignored, Brown lay in bed for four months. One day, Sifford brought heavyweight boxing champ Joe Louis, who loved golf, to visit. Brown was asleep, so the champ left an autographed picture.

Louis wrote on the photo, “Hurry up and get out of that bed so we can kick your butt. Joe Louis.”

Medical personnel paid closer attention after that. Brown was finally diagnosed and treatments began. Each week, he received three injections in his back, the pain so intense it took five people to hold him down. Before one injection, he tried to jump through the window. Dragging his withered body across the room, he collapsed on the floor.

These memories are so unpleasant that Brown winces as he talks.

In 1957, a sort of miracle happened: Pete Brown moved his toes. His therapists began stretching Pete’s legs and he soon was able to make a few tentative steps. Within weeks, he was on the hospital lawn making painful swings with a golf club. Late in 1957, he left the hospital. He had been in bed for more than a year.

Pete went to a driving range and began hitting practice balls. Between shots, he rested in a chair.

“I couldn’t hit the ball,” he remembered. “I missed it a lot. But I had to be in Houston in June.”

To Brown, Houston was the big apple. A tournament there was conducted by the United Golfers Association, the organization that hosted events for black golfers at a time when most tournaments allowed only whites to play.

Brown made it to Houston, but of course failed to play well. That he played at all was miraculous. Over the ensuing months he slowly worked to get his game in shape. It was a great day when he finally won the Lone Star Open. He would go on to win it four times. He captured the UGA’s National Negro Open four times. In 1961, he won the Michigan Open and his grueling stay in the hospital seemed a long time ago.

Now, other threats intruded.

“I wasn’t in contention until the last round,” Brown said. “It was real windy and cold. The last round I shot a 67 and kind of lapped the field to make a playoff. All these people were on the first tee and I was so happy to shoot the 67. We teed off and were on the green when some kids down the street they yelled [a racial insult] and said, ‘Hey! What you doing in there?’ “

So what did Pete Brown do, with all those people there? He laughed.

“Because it was no big deal,” he said. “Everybody started laughing then. You almost have to be nice and they’ll leave you alone. If you challenge them, then you’re in trouble. I learned that back in Mississippi.”

On the second playoff hole, a par 5, Brown hit the green in two shots and two-putted for a winning birdie.

“I was the toast of the town all over Detroit,” he said.

That year, the PGA Tour rescinded its Caucasian-only clause. Sifford already had his Players Card. Brown would earn his card in 1963 but black golfers played the Tour in the shadows. In most towns, they couldn’t stay in motels. They did once, in Lafayette, La.

“The Heberts, Jay and Lionel, ran the tournament and they had the sheriff’s department watch us all night to make sure we didn’t have any problems,” Pete said. “It was a strange feeling.”

In tournament clubhouses, Sifford, Brown and other black professionals were required to eat in dining rooms separate from the club members. White professionals Bob Rosburg, Jackie Burke, Bob Goalby and Art Wall showed solidarity by eating with them.

They had their friends, but desegregation was new and raw, and few expected a black man to win.

It was spring 1964 when the Tour players rolled into Burneyville, Okla., for the Waco Turner Open. Turner, an oilman, was passionate about golf and, even in those days, was considered an eccentric. He carried two .45-pistols and rode around the course on a horse, watching play.

The golf course was long and wide open. Not much trouble. Hard fairways. Right up Brown’s alley. Brown won the tournament. He doesn’t remember much about his landmark victory. Few existing records mention it, but for that week Pete Brown was the best player on the tour and the first black player to win.

When Brown won in San Diego, in 1970, his victory was televised. He beat Tony Jacklin in a playoff. Jack Nicklaus was third. They city of Jackson, Miss., staged Pete Brown Day after that. They had a parade. Gave Pete a fishing boat.

Life in golf was fine. Brown was good to the fans, signed a lot of autographs, spent time with the kids in the gallery. He and Margaret saved their money for the coming years.

“We thought we had everything all set,” Margaret said.

Pete drove from tournament to tournament, sometimes with Sifford, mostly with Ray Fox. They’d practice all day, eat, sleep, play, and practice again. It could be a grind, but it was a good living if you played well. Brown’s official lifetime earnings approached a quarter of a million dollars, good money in those days.

They planned and saved. They thought they were all set.

Still, the racial slights continued. In a tournament in Ohio, a hungry Brown stepped outside the ropes to buy a hotdog. Marshalls wouldn’t let him back in. Tom Weiskopf intervened. “Let the man in,” Weiskopf said. “He’s got to tee off.”

After playing in an exhibition in Florida, Brown slept in his car, worried about threats from the Ku Klux Klan, which was prevalent in the area.

His back pain started in 1964. Pete couldn’t practice, couldn’t tee up the ball. In one round, Dave Hill teed up Brown’s ball. Brown was in severe pain and wanted to quit. Hill told him to finish.

“This course has hard fairways,” Hill said. “All you have to do is get the ball rolling.” Brown finished and won a good check. But a disc problem in his back had begun. It would plague him over the years, easing then recurring over the next decade.

By the end of the 1970s, Brown was playing in just a few PGA Tour events each year. A group from Dayton, Ohio, had approached Brown about taking the head professional’s job at Madden Golf Course, a city-owned layout. They wanted a well-known black professional. Sifford and Elder had turned them down. Brown’s recurring physical ailments made him think it was a good idea. Pete took the job. He and Margaret moved from California to Dayton.

Brown learned the ropes of the club pro’s job. He was wildly popular, a celebrity player at a small municipal course. He had more than 240 mostly inner-city kids in his junior program. He worked at Madden for 26 years. When he retired, they gave him a badge. No pension. No retirement. No benefits.

“They were supposed to pay my way back to California,” Brown said. “They never did.”

A lawyer told Brown it was the worst contract he’d ever seen.

Still, the Browns thought they could make it. They stayed in Dayton, rented a house. Then their daughter got sick.

“When it’s your child, you have to take care of them,” Margaret Brown said. “It took almost everything we had.”

Their daughter died, the second of their six children to die far too young.

Calvin Peete came to visit. Renee Powell telephoned. Still, Pete’s loneliness persisted. Nearly broke and far from old friends, he missed his Southern newsContents. And he was in desperate financial straits.

Last autumn, some of those old friends intervened. Jim Dent, who lives in Tampa, had grown up in Augusta, Ga., and still owns a house there. When Dent, a thoughtful man, heard of the Browns’ plight from Jerry Osborne, a former caddie on the PGA Tour, he offered the house to the Browns.

Osborne contacted other old friends. Some are mentioned in this story. Some are not. Together they raised the money for Pete and Margaret to move. Shortly after Jan. 1, Pete and Margaret Brown drove into Augusta to move into Dent’s rent-free house.

Margaret says she can live anywhere, as long as Pete is there. As for Pete, he seems happier. He’s still infirm but he has found good doctors. Friends visit and Dent drives up from Tampa about twice a month. If the Browns still struggle financially, they are no longer alone.

In March, when we visited the Browns, they were waiting for The Masters to be played in Augusta in April. Surely the Browns would see more old friends. “I hope so,” Margaret said at the time. “Maybe they’ll visit.”

In this game in which strong bonds form, maybe they did.