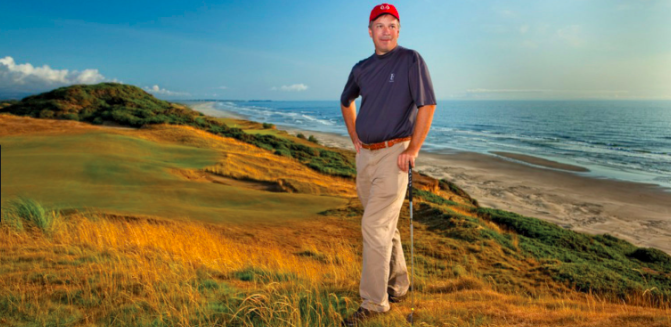

Faces of the NCGA: Architect Tom Doak

August 17, 2021 / by Jerry Stewart

Although he’s a student of the late golf course design legend Pete Dye, Tom Doak’s biggest influence has always been NCGA Hall of Fame architect Alister MacKenzie, whose portfolio includes Northern California gems Cypress Point Club and Pasatiempo GC.

In 2007, Doak helped restore Pasatiempo, which is located in Santa Cruz. Among his most famous designs include Pacific Dunes in Oregon, Ballyneal in Colorado and Cape Kidnappers in New Zealand.

As per his love for MacKenzie, in 2001 Doak penned the book, ‘The Life and Work of Dr. Alister MacKenzie.’ His latest book, ‘The Making of Pacific Dunes’ is now available.

Recently, the NCGA caught up with Doak for a Q&A session.

Q: You are about to release your next book ‘The Making of Pacific Dunes’. Why did you decide to write it? Why should everyone pick up a copy?

D: I don’t know if “everyone” should pick up a copy, but there really isn’t a book by a golf course architect about all of the things he did to build a course and why he chose what he did. What holes were inspired by other courses? What features are natural, and which are constructed? Why did I go left instead of right? It made sense to write about a course that lots of people have played and loved, and from my own work, that’s Pacific Dunes. They’ll be closing in on a million rounds of golf played there in the next couple of years; hopefully a few of those people are curious about the course.

Q: How did the COVID-19 pandemic affect the current projects you have (i.e. visiting sites, zoom vids to discuss progress & challenges, project delays as it relates to COVID travel restrictions and/or supply shortages & increases in material costs, etc.)?

D: I had never once attended a Zoom meeting before March of last year, but I’ve had a few since then!

The pandemic forced developers and clubs to make a decision — keep moving forward with the project or sit on their hands to see what happened. In most cases, if a project had already broken ground, it made sense to keep going, but if it hadn’t, it got postponed. Most of ours were getting ready to start, so they were postponed.

The one that we had more than half built was the new St. Patrick’s Links in north-west Ireland. My associates had just gone back over there last March to get the last few fairways and all of the tees built and grassed, when the pandemic hit, and we had to shut the thing down and let everyone come home. They went back in August to put on the finishing touches, but I didn’t go to supervise it like I normally would; with the greens already finished, I figured my associate Eric Iverson and our team there could handle the rest. I actually came back just this week to see how it’s looking, and I’m happy to say I think it’s some of our best work. It opens to public play at the end of June, and hopefully the quarantine rules for travel will be softened later this summer so that American golfers can come over and discover how beautiful the golf can be in County Donegal.

The biggest obstacle to international work is that the rules about COVID just keep changing, as governments react to every piece of news, pro or con. In the news here yesterday, there was a scramble for UK and Irish tourists to get home from Portugal, because there had been a surge of cases there, and the government decided anyone who wasn’t back by today would have to quarantine when they returned . . . as if the people coming back yesterday weren’t just as exposed.

Q: Can you tell us about any projects you have internationally and when will golf travelers be able to experience those courses?

D: In addition to St. Patrick’s, we have a project in planning just down the beach from Tara Iti in New Zealand — a resort course for the same client. Bill Coore is just finishing his course there now, and ours will get started the first of next year, to be ready for play in 2023. New Zealand is like California without all of the crowds, so there is plenty of opportunity to build on beautiful land that you would never be allowed to touch here — indeed, our client Ric Kayne lives in L.A., but he had to go to New Zealand to get permission to build the course he dreamed about.

Q: In the past several years there seems to be a growing interest from golfers on the topic of course architecture. Why do you think that is and has it given you greater satisfaction in your work than you may have had previously?

D: When I got interested in golf course design, as a teenager, it was very hard to find much to read about it. All of the old books on the topic were collector’s items you couldn’t find at the library. Today, there is just so much more coverage of the topic; between new books and GolfClubAtlas and half a dozen podcasts that talk about golf courses and design, you can literally fall down the rabbit hole and never see daylight again!

I had the great chance when I was 21 to spend a year in Scotland and England and Ireland, learning what golf was really meant to be about, and my way to pay that back has been to sing the praises of the old game whenever I had the chance. So, it’s been lovely to see that influence come back into the game at projects like Bandon Dunes and Barnbougle and the rest.

Q: What makes golf in NorCal so special?

D: There is such a great variety of landscapes to build golf courses on, and the climate is suited to the game — in fact, for someone like me who’s always lived in snowy winter climates, it’s the best place to visit from January to March, if I don’t want to go all the way to Australia.

Q: We’re asking an architect, does the ball need to be rolled back?

D: The problem isn’t just that pros hit the ball longer; it’s that the gap has gotten so much bigger between them and us, so that no amount of forward tees can really compensate for the difference. So, the ball needs to be rolled back for important competitions, and for the people who want to play in them. We need bifurcation in equipment, to overcome the bifurcation in playing ability that the equipment has produced.

You could actually do it other ways, like making elite players go back to persimmon woods with smaller heads — except that most of the players on Tour now developed their game after those disappeared, and half of them would never be able to adjust back away from the game they know. So it’s easier to just change the ball. For everyone else, just keep playing with the equipment you have, until you get to the point that you want to play in competitions with the guys who have to be scaled back.

I actually saw all of that happen once before, when I lived in the UK in 1982-83. The old 1.62-in ball was still in play for amateurs then, it had only been ruled out for The Open Championship and for The [British] Amateur, and mostly because the Americans who came over to play in them didn’t want to have to adjust to playing the small ball, but also didn’t want to give up 30 yards to the guys who played it all the time. Making the American ball bigger for the Amateur was the key, because over time, that restriction moved its way back down the food chain. The guys who had to switch didn’t want to give up yardage to the 2-handicaps in regional competitions, so they made the big ball mandatory for those, too, until eventually, you hardly saw the small ball anymore. The fact that everyone wanted to “play the ball the pros play” became a force for positive change, instead of resistance. I don’t think bifurcation is an ugly word at all.

Q: Who was your biggest influence?

D: Ben Crenshaw was a pen pal of mine from the time I started pursuing a design career in college; he was always generous with his time, and my philosophy of design is probably closest to his. But I learned everything I know about building golf courses from Pete and Alice Dye, and that ability is really what allowed me to have a successful career; without them, I would just have been another guy with an opinion!

Q: What can golf do better?

D: We’ve got to make it easier for women and kids to play golf and find out if they like it, and relax all of the dress codes and other stigmas that scare them away. The only reason I was able to get into golf was that Stamford, Connecticut built a public course a mile from my house when I was nine years old, and the junior rate was $1 after 3 pm. Nowadays, a lot of munis like that are run for the benefit of the loudest senior players, and too many of the privately-developed courses think they have to charge $75 or $100 a head or they’ll go bankrupt. What they need is a bigger pool of players who want to play the course; higher green fees are only sustainable where there is demand for tee times.